by Mark Langley

Efforts to transform the food system have led to increased attention being put on ultra-processed foods (UPFs). But while the term has become a popular shorthand for what’s wrong with modern diets, it’s also a blunt instrument—one that risks obscuring as much as it reveals. Not all UPFs are created equal, and equating processing with poor nutrition oversimplifies complex food science and misdirects investments. In a moment when public scrutiny is intensifying, we need sharper tools—not just louder labels—to evaluate what truly benefits people, animals, and the planet. Not all alternative proteins are ultra-processed, and, as a class, those that are ultra-processed have been found to be healthier than the products they were designed to replace. We welcome a renewed focus on evaluating foods based on their actual health impact rather than the extent of their processing, as the degree of processing is not necessarily predictive of health outcomes in alternative proteins.

TL;DR

UPFs are getting more attention with two books on the subject and a lawsuit against major food manufacturers.

UPFs have been defined by the NOVA Food Classification system.

UPFs have been linked to a variety of health conditions.

UPFs are a proxy for healthy food, but an imperfect one.

Plant-based foods are the first UPFs that are healthier than the products they were designed to replace.

Dr. Greger suggests four approaches to address the UPF debate.

A group of scientists is developing the next generation of the NOVA classification system to consider health factors beyond the processing level.

The Full Story

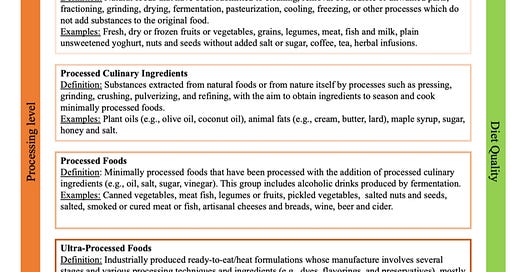

As shown in the Google Trends chart below, the index of searches on “ultra processed food” on that platform rose from virtually no searches until 2019, followed by a sudden onrush of interest:

Google Trends Chart of “Ultra Processed Foods” Searches (Indexed) from 1/1/2015 to 2/11/2025

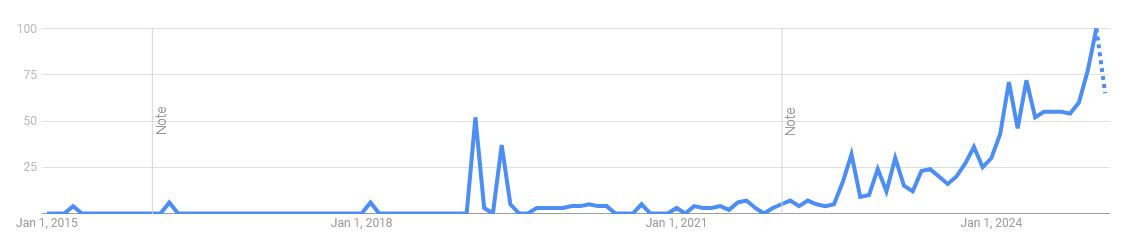

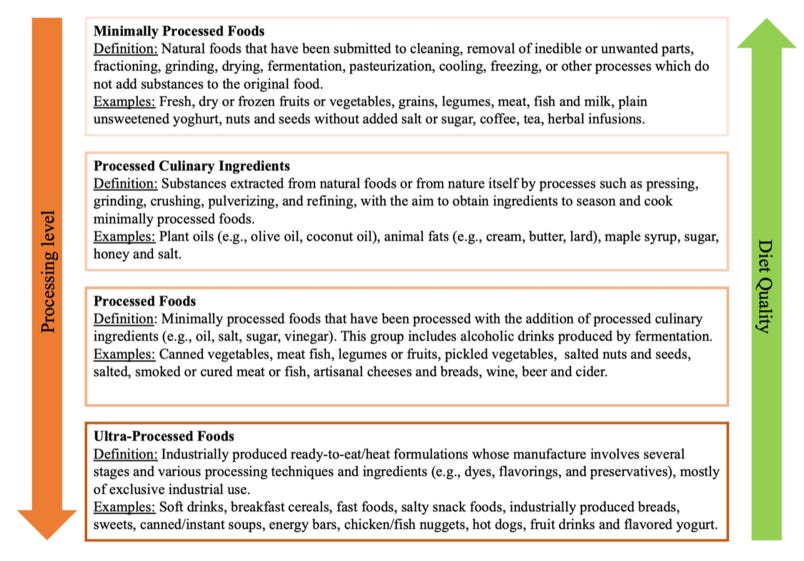

The NOVA Food Classification system defines ultra-processed foods (UPFs) as being “industrially produced ready-to-eat formulations whose manufacture involves several stages and various processing techniques and ingredients (e.g., dyes, flavorings, and preservatives), mostly of exclusive industrial use.

UPFs have been linked to a variety of health conditions, including several leading causes of chronic disease (colorectal cancer, type 2 diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular disease, digestive issues, hypertension, liver disease, and dementia), with some calling them a global threat to public health.

Plant-based diets have proven to be more nutritious than animal-product-based diets, and they benefit heart health, weight management, diabetes prevention and management, reduced cancer risks, longevity, and digestive health. Recently, though, alternative (“alt”) proteins have been attacked for (sometimes) being highly processed, which has muddied the waters for those who choose to focus on healthier foods. While alt proteins can be highly processed, they stand out from other highly processed foods because they are better than the products they are designed to replace (more on this below).

Why, then, are alt proteins being lumped in with processed junk foods?

The internationally recognized NOVA Food Classification system, designed by the Center for Epidemiological Studies in Health and Nutrition at the University of São Paulo, Brazil, classifies all foods and food products, according to the extent and purpose of the industrial processing they undergo, into four groups:

unprocessed or minimally processed foods,

processed culinary ingredients,

processed foods, and

ultra-processed foods (UPFs).

The usefulness of the classification system for informing dietary guidelines has been debated (see here and here, for example), and stakeholders on both sides have voiced concerns, leading to potential changes in food policy.1

Some fears about UPFs are reasonable. Studies involving nearly 10 million people have shown that greater exposure to ultra-processed foods is associated with a higher risk of various adverse health outcomes.

The NOVA Food Classification is depicted below:

However, alt protein UPFs, which are designed to replace their less-healthy counterparts, are often unfairly judged or categorized as being the same as most UPFs, despite being distinctly better:

In a survey of nearly 10,000 consumers across 17 European countries, half said they avoid plant-based substitutes because they are ultra-processed foods.2

Recently, Dr. Michael Greger3 responded to this concern. Nearly 1,000 papers (available here) informed his findings. I will share a few highlights of Dr. Greger’s talk, in which he reviewed this body of work.

Sixteen factors of concern have been identified by the developer of the ultra-processed food classification system that show why increased consumption of UHP foods might lead to increased disease and death4:

Using these criteria, a minimally processed food is compared with processed food, and the UHP food tends to do worse (e.g., see “fruit candy” vs. “fruit in the table below), and not just because of the nutrient profile (which occupies only the first row of the table):

However, as Dr. Greger painstakingly explains, plant-based meat alternatives appear to be better in most ways than the products they were designed to replace.

For example, a 2024 systematic review found nine studies comparing the nutritional quality of plant-based meat to animal-based meat products using a variety of different nutrient profile systems (i.e., scoring systems), and they all found that ultra-processed meat alternatives scored mostly better — healthier than conventional meat based on every nutrient scoring system tested.5

Sodium content is commonly cited as a concern with plant-based meat and an area for improvement. Sodium is added for structure and taste during the development of some soy products, but it is also introduced via the use of acids and bases during the fractionation process of soy protein isolates. Dr. Greger notes: “Reduction of the amount of sodium present in meat alternatives should be a top priority in the reformulation agenda, perhaps by using potassium hydroxide instead of sodium hydroxide in the protein fractionization process.” Product developers have taken note. The use of Ca(OH)2 instead of NaOH during an alternative mild fractionation process can increase calcium content and reduce sodium content, and the findings are expected to work with other common protein isolates.6 Still, as the 2024 systematic review noted, the saltiest plant-based sausage was found to be less salty than the least salty meat sausage.

Swapping even one serving of plant-based meat per day nationwide could potentially prevent more than 100,000 cases of heart disease, stroke, and cancer in the United States every year.7

Dr. Greger also reminds consumers of other harmful content in animal products, including feces, prions, antibiotics, toxoplasma, tapeworms, Salmonella, Campylobacter, cancer-causing viruses, and cancer-promoting growth hormones, trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), cholesterol, saturated fat, and industrial contaminants that bioaccumulate in animal tissues, including certain pesticides, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), heavy metals and flame retardants. This content doesn’t show up in ingredient decks. He adds: “When researchers tested retail meat for the presence of 33 chemicals with calculated carcinogenic potential, like organic chlorine pesticides and dioxin-like PCBs, they concluded that in order to reduce the risk of cancer, it was suggested limiting ingestion of beef, pork, or chicken to a maximum of five servings a month.”

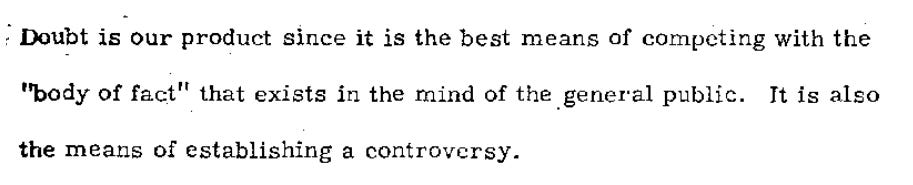

The confusion that equates alt proteins with other ultra-processed foods is often purposeful, and the push for UPF concern can be traced back to animal industry advertising and misinformation campaigns.8

So, what should we do in the face of this attempt to undermine alt proteins?

Dr. Greger proposed three possible tracks to address the UPF critique when lobbed against alternative proteins and highlighted the second as the most constructive (paraphrased from his discussion):

Do not use the UPF label. Decry the ultra-processed label by parroting “the false industry narrative,” suggesting a lack of consistency in categorizing ultra-processed foods. Why “false”? He notes that the study that claimed the label was ambiguous used untrained individuals, whereas independent research showed that trained individuals disagreed less than 5% of the time.

Acknowledge UPF, but also note that alt proteins are standouts. Don’t deny that ultra-processed foods tend to be worse or that plant-based meats are ultra-processed. Rather, despite this classification, plant-based meats are the rare exception: they compare well with the foods they were designed to replace, potentially saving thousands of lives.

Take a “throw the babies out with the bathwater” approach to the ultra-processed concept. The latest dietary guideline for the American Heart Association recommends avoiding ultra-processed foods, but they do have an asterisk stating that some healthy foods may exist within the ultra-processed food category. This is also a compelling argument against animal-based foods. Three Harvard cohorts involving 200,000 people followed for decades showed that total ultra-processed food intake was associated with cardiovascular disease. However, that was driven by soda and meat: sugar-sweetened beverages and processed red meat, poultry, and fish. When soda and meat were excluded, the relationship between ultra-processed foods and cardiovascular disease disappeared. What about mortality? When it came to premature death, the apparent worst ultra-processed foods were meat, poultry, and seafood. What was the worst when it came to dying from cancer, cardiovascular disease, lung diseases like emphysema, and other causes? Meat, poultry, and seafood. But that does not mean you can live on vegan donuts.

NOVA was established in 2009, but the UPF claim against alt proteins rose in prominence when a PR organization initially funded with “tobacco-company and restaurant money to fight smoking curbs in restaurants” and which has a long history of making false and outlandish attacks, focused its efforts on creating UPF doubt in alternative proteins.

Then, it became more newsworthy with a landmark lawsuit filed by an 18-year-old plaintiff on December 10, 2024, which accused major food corporations of causing widespread health issues by manufacturing and marketing ultra-processed foods. We do not believe that plant-based meats were the suit's focus; however, the UPF label tarred it with the same brush.

Uncertainty is an inherent part of science, and understanding the health risks of chemicals in food can be particularly challenging. Manufactured uncertainty is another matter entirely. As in other industries, groups with vested interests often put their “fingers on the scale” in the investigative process when their interests are threatened. It would appear that some animal agriculture flacks are borrowing tactics used by the tobacco industry in 1969 when an executive at Brown & Williamson, a cigarette maker now owned by R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, unwisely committed to paper a slogan for his industry’s disinformation campaign in this intra-office memo:9

In summary, the UPF characterization could help alt proteins because it brings with it a “body of fact.” But it may also be a threat (from the perception of being less healthy than the products they are designed to replace), the large body of work showing that alt protein UPFs are more nutritious, notwithstanding. This issue may become more prominent, particularly if UPFs are considered a “Front Of Package” (FOP) issue.

Alt proteins still face the challenges of cleaner labels, intensive processing, texture, flavor, and lower costs. Furthermore, fermentation-derived protein technology must address many system limitations and regulatory approvals. Ultimately, staying within the planetary boundaries and under 2°C warming relies on multiple strategies. But these are manageable engineering challenges, and alt proteins are one of the best solutions for reaching a nutritionally healthy, safe, efficient, affordable, sustainable, and inclusive food system.

For example, related topics are addressed in US 118th Congress bills, which either would require FDA to reassess the chemicals contained in foods or FDA’s GRAS determination process (e.g., H.R. 9817, H.R. 7588, H.R. 3927, S. 3387). Other legislation broadly seeks to update existing food labeling requirements (e.g., H.R. 2901/S. 1289) as well as require additional labeling of certain ingredients and products containing sugar, sodium, and saturated fats (e.g., H.R.6766/S. 3512, S. 4195). Available here.

Food, E. I. T. "Consumer Perceptions Unwrapped: Ultra-Processed Foods (UPF); European Institute of Innovation and Technology (EIT): Budapest, Hungary, 2024."

Dr. Greger is a physician, New York Times Best-Selling author, and internationally recognized speaker on nutrition, food safety, and public health issues. He founded NutritionFacts.org.

Source: Monteiro, Carlos A., Arne Astrup, and David S. Ludwig. "Does the concept of “ultra-processed foods” help inform dietary guidelines, beyond conventional classification systems? YES." The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 116.6 (2022): 1476-1481. Available here.

Lindberg, Leona, et al. "The environmental impact, ingredient composition, nutritional and health impact of meat alternatives: a systematic review." Trends in Food Science & Technology (2024): 104483.

Peng, Yu, et al. "Effect of calcium hydroxide and fractionation process on the functional properties of soy protein concentrate." Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 66 (2020): 102501.

Dr. Greger, using data from: Springmann, Marco. "A multicriteria analysis of meat and milk alternatives from nutritional, health, environmental, and cost perspectives." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 121.50 (2024): e2319010121.

Source: Changing Markets Foundation (2024). “The New Merchants of Doubt: The Corporate Playbook by Big Meat and Dairy to distract, delay, and derail climate action”

Source: Glantz, Stanton A (1996). The Cigarette Papers. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-520-92099-6. OCLC 42855812. https://www.industrydocuments.ucsf.edu/docs/psdw0147